Welcome to the Clinical Review/Primary Care. It consists of four unique case studies. After reading through each, you will have the opportunity to answer several questions about your treatment of each patient.

Read the Introduction below, then click on “Case Study 1” from either the link at the bottom of the page or from the menu above to get started.

Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 ASCVD is also the leading cause of morbidity and mortality for individuals with diabetes. ASCVD results in an estimated $37.3 billion in cardiovascular-related spending per year associated with diabetes in the United States alone.2

Common conditions that coexist with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) such as hypertension and dyslipidemia are clear risk factors for ASCVD. At the same time, diabetes itself carries independent risk for ASCVD.

About 12% of U.S. adults have diabetes; 90% to 95% of them have T2DM. More than a third of U.S. adults, about 80 million individuals, have prediabetes and are at risk of developing T2DM.1 On a global scale, about 60 million Europeans are thought to have T2DM, half of them undiagnosed, as does about 10% of the population of countries such as India and China, which are embracing increasingly Westernized lifestyles.3

The cumulative result is an estimate of more than 600 million individuals with T2DM worldwide by 2045 and another 600 million developing pre-diabetes.4

Multiple randomized controlled clinical trials have shown that controlling individual CVD risk factors can slow or prevent ASCVD in individuals with diabetes. Addressing multiple risk factors simultaneously confers even larger benefits. There is evidence that the current approach of aggressive risk factor modification in patients with diabetes has significantly improved measures of 10-year coronary heart disease risk among U.S. adults with diabetes over the past decade and that ASCVD morbidity and mortality have decreased in this population.2

Heart failure (HF) is another major cause of morbidity and mortality from CVD, particularly for individuals with diabetes. Rates of incident heart failure hospitalization are twofold higher in patients with diabetes compared to those without diabetes after adjustment for age and sex. Those with diabetes may have heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) or with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Hypertension is often a precursor of heart failure of both types, and ASCVD can coexist with either HFpEF or HFrEF. Myocardial infarction (MI), by contrast, is often a major factor in HFrEF. Major trials have shown treatment with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) can improve the rate of heart failure hospitalization in patients with T2DM (potentially reducing rehospitalization), most of whom also had ASCVD.2

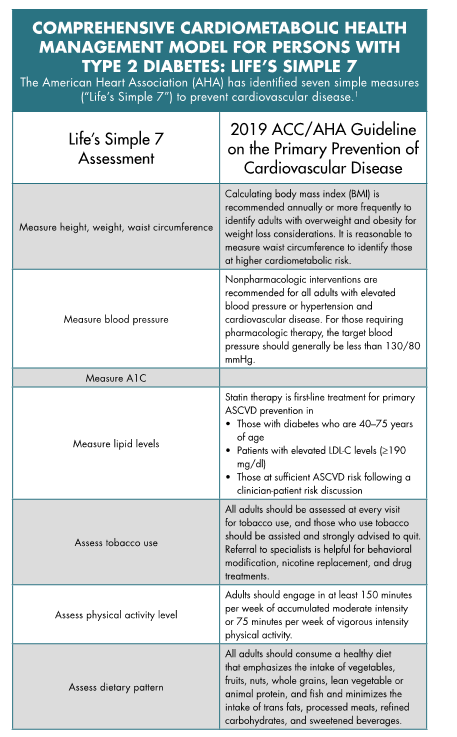

Cardiovascular risk factors should be systematically assessed at least annually in all patients with diabetes for the prevention and management of both ASCVD and heart failure. The most common risk factors include obesity or overweight, hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, a family history of premature coronary disease, chronic kidney disease and the presence of albuminuria.2

Hypertension, defined as sustained blood pressure ≥130/80 mmHg, is commonly seen in patients with any type of diabetes and is a major risk factor for both ASCVD and microvascular complications of diabetes. Blood pressure targets can be adjusted for individual factors.

Hypertension, defined as sustained blood pressure ≥130/80 mmHg, is commonly seen in patients with any type of diabetes and is a major risk factor for both ASCVD and microvascular complications of diabetes. Blood pressure targets can be adjusted for individual factors.

In general, in individuals at higher cardiovascular risk, a blood pressure target of <130/80 mmHg may be appropriate if it can be attained safely. For individuals at lower risk for CVD, a target of <140/80 may be appropriate.5

For all individuals with blood pressure >120/80 mmHg, lifestyle management, including regular exercise and close attention to weight, is an important component of treatment. If overweight/obese, weight loss through calorie restriction is appropriate. A Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)- style eating pattern, moderation of alcohol intake and increased physical activity are appropriate.5 A diet emphasizing intake of vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, whole grains and fish is recommended to decrease ASCVD risk factors.6 Pharmacotherapy can be an appropriate second-line therapy for individuals who fail to respond to lifestyle intervention.

Between 20% and 40% of individuals with diabetes will progress to diabetic kidney disease. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) typically takes about 10 years to develop in type 1 diabetes but may be present at diagnosis for T2DM. Having CKD increases cardiovascular risk and health care costs for all types of diabetes. CKD is also the leading cause of end-stage renal disease in the United States, which requires dialysis or kidney transplantation.7

CKD is diagnosed by the continuing presence of albuminuria, low estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) or other evidence of kidney damage. SGLT2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP1-RAs) have been shown to reduce the risk of CKD progression, cardiovascular events or both.7

Appropriate treatment of diabetes and associated comorbidities is based on a close working relationship between the patient and the care team. A patient-centered approach that uses active listening, focuses on patient preferences and beliefs and assesses potential barriers to care can optimize patient outcomes and quality of life related to health. Individuals with diabetes must take an active role in their own care and in the decisions relating to their care.8

The patient, with family or support group and an interdisciplinary team, should formulate a diabetes management and care plan designed to prevent or delay comorbidities and maintain quality of life. The care team can include primary care providers, specialists such as cardiology, nephrology or endocrinology as appropriate, nurses, diabetes educators, dietitians, exercise specialists, pharmacists, dentists, podiatrists, mental health specialists and other providers as needed.8

Health care providers should provide a referral to a Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support (DSME/S) program for newly diagnosed diabetes patients, annual assessment, new complication factors (physical, health status, emotional or basic living) and when transitions in care occur. These programs with the support of a Certified Diabetes Educator provide the foundation to help people with diabetes to navigate these decisions and activities and has been shown to improve health outcomes.9

DSME/S has been shown to be cost-effective by reducing hospital admissions and readmissions as well as estimated lifetime health care costs related to a lower risk for complications.9 Medicare and most insurance plans cover the cost of DSME/S.

The risks of ASCVD and heart failure, CKD and other complications together with assessment of other acute and chronic complications can be used to individualize targets for glycemic control, blood pressure and lipids. Those same factors can be used to select the most appropriate lifestyle modifications and, as needed, pharmacologic interventions.8 Aggressive risk factor modification using strategies that affect multiple risks simultaneously is more effective than controlling individual risk factors.2